I recently had a marvelous experience at St. Louis's oldest theater, the Hi-Pointe, where I went to see The Martian (2015) by myself in an afternoon. I've passed the place a thousand times and nearly all my friends have been there, but I had never gotten up and gone myself. Not ten minutes went by inside that building before it became my favorite theater in Saint Louis. A classic marquis outside advertises the two films it plays a week. A ticket booth juts out of the building. You walk in to a tiny, tiny lobby with one or two table and chair setups in front of a minuscule concession stand with one lone, mustachioed employee ready to tell newcomers where the bathrooms are. They are up a rickety flight of carpeted stairs that begins in a far corner of the lobby. You take a tour of old Hollywood posters and photographs to get there. At the top of the stairs sits a pedestal with a bowl of hard candies. The men's room is at the end of the narrow hallway. The urinals are of the ancient, long design, like this:

A huge window spans the north wall of the restroom, allowing you to see the downtown STL skyline in the distance and the world's largest AMOCO sign next door. Back in the lobby, there's a small alcove tucked away, adjacent to the theater entrance. A neon green sign saying "It's cool inside" illuminates the space in an eerie, Lynchian glow.

The theater is a simple, three-sectioned auditorium that smells vaguely of old chemical cleaner and is dimly lit by classic theater lamps. The screen is hidden by a rumpled turquoise curtain that parts when the trailers begin.

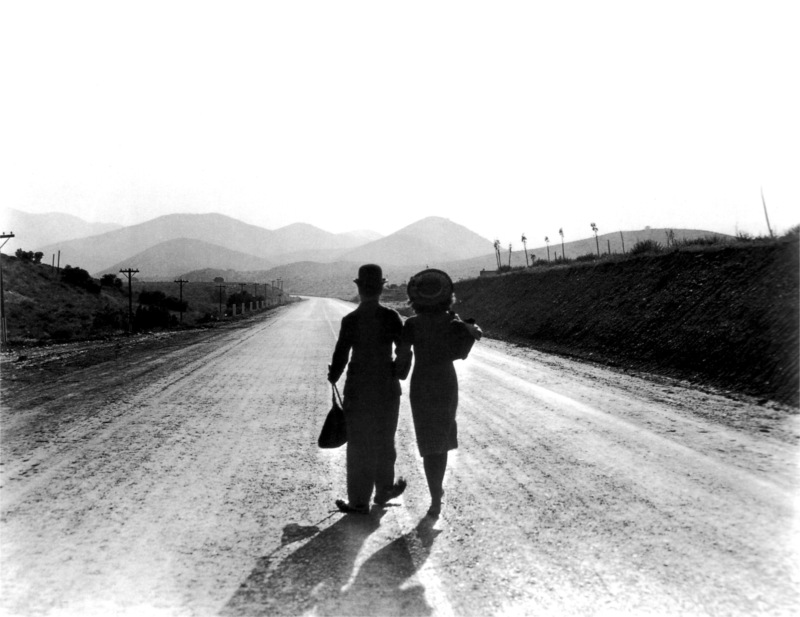

Basically, I feel like a depression-era youngster catching a two reeler at the nickelodeon as an escape from my troubles when I'm in there. Not only that, but the theater is a skip away from forest park, hosts films for SLIFF, and is named for the Hi-Pointe neighborhood which is the highest altitude in Saint Louis. So it makes me feel absolutely at home, too.

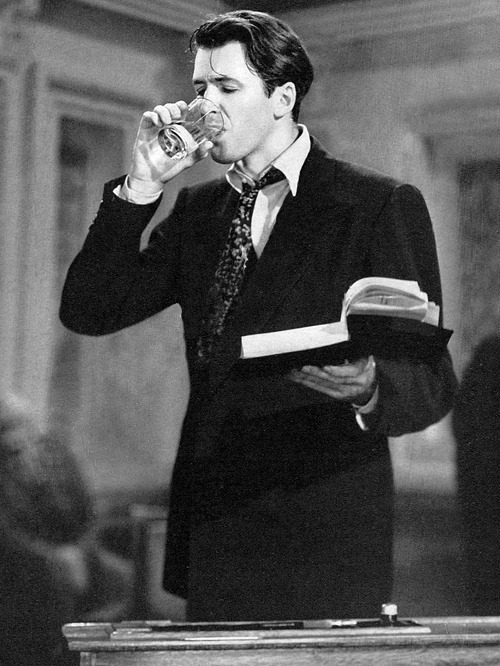

These feelings lent themselves to my experience watching The Martian. One of the initial things that I admired about it, something the film has in common with The Maltese Falcon, was that it wastes no time on exposition. You might get two minutes at the most of set-up, which is mostly just a visual introduction to the Mars setting, before the storm hits and leaves Matt Damon completely stranded. The movie just gets going right away. All the back story, relationships, and contextual details are dropped in subtly as the plot progresses. It's rather elegant. That's something I admire about many older films, especially film noir. They really don't waste any time. The inciting case that drops into the lap of Spade, played by Bogart, gets the story going before you even know the main characters' names. You don't stop learning things until the very end of the movie.

At the same time, film noir movies have always been a little difficult for me. The plot points zip by, new characters are constantly being introduced, the dialogue is light speed fast. The first viewing of a film noir film, as visually stunning as they often are, is usually a slightly stressful experience for me. The first time I saw The Third Man, I couldn't quite keep up with the plot. I could appreciate the score, the visuals, the brief but excellent performance by Orson Welles, but I was left a little flabbergasted and underwhelmed. I then went to see a 4k digital restoration of the film in a theater. Having the basic plot in mind and knowing all the characters, I was able to look at the details, analyse the writing and the themes, and let myself get caught up in the atmosphere, aesthetic, and ideas progressing in the narrative because I wasn't so focused just trying to keep up with the basic story line. Now it's probably in my top 10. I suspect my second viewing of The Maltese Falcon will produce similar results. My experience watching it for this blog was a bit laborious, because it is one of the most stylistically noir films of its time in all the good ways and all the challenging ways.

A beautiful and mysterious woman in a tight skirt and an omen of a black hat, the ultimate vision of a femme fatale, walks into a chain smoking PI's office. She asks him to tail a man who has her sister, and those of us in the 21st century know her story is totally phony. She wants to keep track of the man. There is no sister.

Our characters constantly smoke, sometimes in each other's faces, bringing to mind Out of the Past, another film noir of which Roger Ebert said, "There were guns in Out of the Past, but the real hostility came when Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas smoked at each other." At one point, Spade blows smoke right in the face of Wilmer, who was tailing him.

Lots of shit goes down in the first ten minutes. Spade and his partner, Archer, get a request by the mysterious woman to follow someone. Archer gets killed while investigating, all signs pointing to the man he was supposed to be following being the murderer. But later, Spade finds out that very man, Floyd Thursby, has been killed as well. Archer's wife, who Spade is having an affair with, wasn't home during the shooting. The mysterious woman is not who she said she was.

Spade is following all these leads and getting followed himself. He meets with a bunch of contacts, has run-ins with the cops and learns new information. Yet this doesn't clarify as much as it should. because the film has set up a world that can turn upside down at any moment.

The tables incessantly turn in a classic film noir, and there are several scenes, here, where the tables turn frequently within one scene. Most memorably, a gun shifts hands multiple times between Spade and the mysterious Joe Cairo, played by Peter Lorre.

Most interestingly, the movie offers us a protagonist that is rarely seen in films of the time. I'd contend that in most film noir (excluding neo-noir and other derivatives), we can always side with the protagonist. In a film like The Third Man, the main character is almost totally innocent and compassionate. In Out of the Past, there's a lot of pathos in Robert Mitchum's performance and the film is constructed on a technical level so that we are always close to him. He makes a lot of questionable decisions, but he always keeps his audience's faith. In The Maltese Falcon, Spade is self-assured, reckless, and a bit of a backstabber. Early on, we begin to question if we can trust our own protagonist, is he's reliable, and if he's the kind of person you want to root for.

We already know he's seeing his partner's wife, showing a complete lack of respect for him as a person. This flows into a disregard for the partner's well-being, too. The scene where he learns of his partner's death is indicative of this among other less than positive things about Spade.

I didn't understand, at first, the choice to point the camera away to the nightstand when he receives the news. But watching the rest of the movie reveals how this visual helps characterize Spade quite a bit early on. He sleeps with his window open. No man so close to the edge of the dark urban underbelly of society would be so careless. Soon after, he reveals he doesn't carry a gun (despite knowing all about them and how to use them). Unless you're Mike Ehrmantraut, you gotta be packing if you're gonna be a hardcore PI.

What this shot also does is reveal a seeming apathy in Spade's reaction to Archer's death. It doesn't even show him get the news. You only hear it, and his voice makes no indication of grief of surprise. It's an emotionally sterile moment for what is tragic news. When he does move into frame, his face conveys more annoyance and pensiveness than shock or sadness.

| That's a subjective reading. It's a face. |

To compensate for this, the film gives you no other characters to side with. Spade is the lesser of all the evils. It's a tumultuous relationship the film gives us to Spade, though, because aside from his unreliability, Spade really starts to seem crooked after a while.

First of all, the plot is so fast paced and complex that it's hard to remember why Spade got roped into all this in the first place. His partner was killed by one of these people or someone associated with them, but the fact that they drew the partner in to get killed in the first place raises some questions. It's all over this Maltese falcon figurine, and it should have been between this mysterious woman named Brigid, Joe Cairo (Lorre), Gutman and his bodyguard Wilmer. Bringing in an outside party only serves to complicate things. Ultimately, there are small but definite reasons and events that incite Spade's involvement in the first place, but it's so remote in the story-line that we often forget, and this entire journey starts to become existential.

This isn't a bad thing. While we're trying to remember why Spade's involvement in this Maltese falcon heist scheme is necessary and why he's really in this situation, Spade, himself, begins to lose sight. Without us really noticing it at first, Spade's investigation into his partner's death turns into a pursuit to outwit Gutman, Brigid, Cairo and Wilmer. They are now his competitors for this statue. He starts taking money offers, forging deals, and strategizing to get the upper hand in the game. By the end, he's so obsessed with keeping the falcon hidden and getting paid a proper amount to put it in the hands of Gutman that it dawns on us that he no longer has any interest in justice--only money. Greed has overcome him.

SPOILER

I don't normally include spoiler tags, but this is a last minute turn around so I thought it necessary. Spade is overcome by greed...until the very, very last minute. We see that the falcon he has given them is fake, probably swapped out by the one of the crew members on the boat transporting it. Spade initially insists to keep his money, but gives it back up with little persuasion, keeping only 1,000 of the 10 grand he was supposed to get. He then turns in Wilmer, Gutman, and Cairo and uses the 1000 he kept to implicate them in bribery. Despite having romantic feelings for Brigid, he turns her in as well when he figures out she killed Archer to frame Thursby and cut him out of the deal. So all along, this lack of control, greed, and recklessness was a beautiful, intricate, masterful facade that Spade used to get to the truth and make sure justice was served. The movie turns everything upside down one last time.

What's more interesting is it doesn't have to be read that he did it to avenge Archer. No, his actions still show an absolute disrespect for the man. He does it just because he can. He needs to know the truth, he thrives on it. Brigid and Cairo and Gutman's secrecy and treachery is a mere challenge to Spade. Spade's purpose in life is to find the truth. He's a private investigator not by mere profession but by passion. Even in those emotional crossroads of human experience, he goes with the truth, never comfort or happiness.

It's one of the more interesting and surprising character arcs I've seen. That's, like, meta-unreliable narrator or something. I mean, Spade isn't a narrator but the movie is centered around him, and he's a bit of a weasel. For the film to have this character that is already unique in his questionable morals and then turn it around on us and show us that he is actually the anti-thesis of unreliable is pretty impressive and clever.

Film noir is a deep and complicated chapter of American cinema. I haven't seen them all (has anyone?) but not only does The Maltese Falcon embody almost all of its classic traits, it's also one of a kind.